In which we talk with Marina about the movement for reparations for victims of the Spanish Civil War and of the Francoist dictatorship.

Description

In this episode we talk with Marina Díaz Bourgeal, who is an ancient history PhD candidate, about the Spanish Civil War and the 40 years of Francoist dictatorship in Spain, about the movement for reparations of its numerous victims, and about Marina’s family history and the ways it is entangled with Spain’s history. The discussion starts with a brief history of the Spanish Civil War, its major actors and the role of unions in the war. Next, we learn about the movement for reparations, whose mission is the public recognition of people who have fallen during the civil war and whose burial places are still unknown. In the second part of the episode, Marina tells us about her family history. We learn about how various family members have participated in the civil war and what their fate was in the post-war period, and generally how the story of her relatives is entangled with and reflects the history of Spain during the last 80 years.

(Re)Sources

- Interview with F. Montseny (use auto translate subs)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pV5Qbb7Im9c

- Juan Garcia Oliver in 1937, about Buenaventura Durruti

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxBWAbKQfSE

- Valle de los Caídos / Valley of the Fallen

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2b/Valle_de_los_caidos.jpg

- Mass graves in Spain

- V2.1

- https://www.lasexta.com/noticias/nacional/mapa-verguenza-espana-todas-fosas-comunes-victimas-guerra-civil-franquismo_201902265c7553260cf2e60c4243c6c5.html

- G. Orwell. Homage to Catalonia (1938).

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/9646.Homage_to_Catalonia

- K. Loach. Land and Freedom (1995).

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114671/

- V. Aranda. Libertarias (1996).

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0113649/

- M. Ackelsberg. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women (1991).

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/450577.Free_Women_of_Spain

- E. Goldman. Vision on Fire: Emma Goldman on the Spanish Revolution (1983). ed. D. Porter

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/239440.Vision_on_Fire

- P. Broué & É. Temime. The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain (1961).

- https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1852121327?book_show_action=false&from_review_page=1

- Ronald Fraser. The Blood of Spain (1979)

- https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1700115928?book_show_action=false&from_review_page=1

- D. Graeber. Debt : The first 5,000 years (2011) — R.I.P. David Graeber :(

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6617037-debt

- Selection of Spanish Revolution and Civil War songs

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yo-49-d-7w4&list=PLze-Vv3Izj5mq72XpsX7hSXzU3C1pLq3p

- Recent developments

- https://english.elpais.com/spanish_news/2020-09-15/spain-drafts-bill-against-remaining-legacy-of-franco-era.html

- Artwork by Casandra Ciocan

- https://www.behance.net/casandra-ciocian

- Sloth metal riffs by Zomfy

- Intro/Outro song: ¡No pasarán! by Sofia Zadar

- https://www.facebook.com/sofiazadar/

- https://open.spotify.com/artist/3F4Ec4iFdVp4Pmzhw2Zrd1

Trascript

ioni: [00:01:00] Hello, everybody, welcome to a new English episode of Leneșx Radio, Sloth Radio. I'm Ioni, your host for today. And with me here are Robi and Lori.

lori: [00:01:15] Hello again.

ioni: [00:01:17] And our returning guest host, Andra.

ioni: [00:01:22] The guest of our show today is Marina.

ioni: [00:01:27] We'll do like a micro historical overview of her family history and how it connects to the last 80 years or so of Spanish history, starting all the way from the Spanish Civil War and up to the family’s return to Spain.

robi: [00:01:46] Before moving on to the episode itself, let's just give a shout out to everyone who contributed in some form or other to this episode. First of all, a big thank you to Sophia Zadar, for this fabulous adaptation of the song No Pasaran. If you don't manage to get through the whole episode, we know it's pretty long, please don't leave before jumping to the end and listening to the song. It's really wonderful. We use various soundbites from Kevin McLeod's website. And finally, the artwork of this episode is by Cassandra Ciocian, who is a wonderful artist and illustrator. You can find some links to their work in the description of the episode.

robi: [00:02:28] That being said, we hope you enjoy the episode

marina: [00:02:57] I am a PhD candidate in ancient history, here in Madrid. I work mainly with social history and cultural history, but I am also very interested in the political uses of the past. That's maybe the reason why I have always been curious about the past of my family. And that may also be the reason why I engaged with politics rather early in my life, but especially since the anti-austerity movement here in Madrid, which started in 2011 with the 15-M movement, the Moviemento 15-M.

ioni: [00:03:33] Before we begin, maybe you can tell us a bit about the current political climate and situation in Spain, because even during our previous episodes, we try to see what's happening with the pandemic and everything going on. I mean, there's this rising nationalist, somewhat far right sentiment everywhere, while other people are constantly criticizing us for being a bit too paranoid and overstating what's happening. But, you know, an old saying on the Internet says that just because you're paranoid that doesn't mean they're not out to get you.

ioni: [00:04:09] So what's happening in Spain right now?

marina: [00:04:12] Ok, so the situation is getting slightly better, but it has been a really difficult period for the whole country, but especially for common people. We have now twenty seven thousand deaths by coronavirus. We still have cases every day, but much less than before. And the whole situation has caused high unemployment rates. Many people have lost their job and are surviving with the help of different NGOs or mutual aid organizations. For example, here in Madrid, the situation in the south neighborhoods of the city is quite difficult. If you look for the news in the newspapers in May and April, you can see a lot of photographs of really, really long lines of people waiting for different NGOs to give them food. And very recently, the parliament approved what they have called the increase of the minimum survival income, which is like a really soft version of the idea of universal basic income.

ioni: [00:05:21] You also told us before and during our short discussion something about the former right wing -- currently moving towards the far right -- party and their weird shenanigans, so maybe we can talk about that for a bit before moving on to the main discussion?

marina: [00:05:41] Yes, of course.

marina: [00:05:42] I mean, it was really striking for me and for many other people to see that at the same time, long lines of working class people were waiting for food in different places of Spain. In the city center in Madrid, in the Salamanca district -- which is one of the districts in Spain with highest income -- lots of people were demonstrating in the streets because they wanted more freedom. And nobody knows what this freedom will be about. Maybe to, I don't know, go to their local Tommy Hilfiger shop and buy. I'm not sure. But they were demonstrating at a moment where demonstrations were technically not allowed. And in other places of the country, the police was interrupting these kinds of demonstrations, but not in Madrid. So it was a really funny situation because they were demanding more freedom. They were demanding their right to go back to the streets and to reopen their businesses. At the same time as many, many doctors were risking their lives in the hospitals, helping people not to die. So it was really striking.

ioni: [00:06:49] We should take this opportunity to also express our solidarity with the Capitol Hill autonomous zone. The CHAP, or CHOP or CHAZ. Haven't they changed the name to CHOP?

ioni: [00:07:02] And Fox News was doctoring some pictures to make it seem like there was a lot of violence going on and like there were armed thugs and violence in there. And this instantly brought to mind the thing you told us about the doctored pictures that the Spanish far right did. So maybe talk about this a bit.

marina: [00:07:20] Yeah, I think it was in March, at the end of March, there was this Spanish photographer -- Ignacio Pereira -- who is famous because he focuses on taking photographs of urban spaces which are completely empty. Yeah, they are completely empty. So he took a photograph of the main street in Madrid -- Gran Via. I don't know if you have heard of the street, but it's always full of traffic, people moving, going to work or to school. It's a really, really hectic place in Madrid. And he took a photograph of this place completely empty. The only person you could see in that photograph was a delivery person or just a worker. So somebody who was bringing food to somebody else. This was a really, really viral photo in the Twitter scene in Spain. I mean, I'm not into Twitter, but I have friends who are really active Twitter users. And it was all around Twitter for many days.

marina: [00:08:20] And then the main far right Spanish party -- VOX -- made a version of the photograph with a street full of coffins, with the Spanish flag in the coffin. And they uploaded the photograph saying something like, many Spanish citizens are getting creative during this really difficult time. Then the photographer, who is also a really active Twitter user, saw the photograph and said, hey, guys, this was not meant like that. This is not the topic which my photograph is about. And apparently he has demanded this of the party. Because they were misusing the photograph, which originally have a really different message, which was when everything is completely stopped, it's the common people who are still working for the rest of the country.

lori: [00:09:16] You know, it's a bit ironic that the very people who go to protest their lack of freedoms in this case would be literally the first people who would complain about either working people or marginalized groups trying to protest.

marina: [00:09:30] Yeah.

lori: [00:09:31] And this happens now, which is also paralleled by and would readily call for state repression of these protests or strikes, which is readily paralleled with what happened before and during the Spanish Civil War.

marina: [00:09:46] Yeah, it's also interesting that ... I mean, this government we have now in Spain won the elections last November. After a long time without a proper government. Because we had to go to elections, I don't remember if it was once or twice, before we got a proper government. And it's a coalition of the Spanish Socialist Party, and Unidas Podemos, which is, as well, a coalition of the Spanish equivalent of die Linke, and Podemos party, which emerged from the anti-austerity protests in 2011.

marina: [00:10:24] And this is the government, the first government in democracy, I would say -- in the Spanish democracy, since the end of the 70s -- which is taking seriously the idea of historical memory. The idea that we need to somehow recognize the fight of the many people who died during the 30s here in Spain and afterwards during the dictatorship, trying to defend the idea of democracy. Different ideas of democracy, of course. And of course, the corona crisis is a perfect scenario for the different right parties to criticize this government for many, many different things. Their favorite nickname, that the right say the most, is that all these measures they are taking due to the crisis are communist measures or even better Chavist measures. So measures that the government of Venezuela will take as well. So, yeah, the Spanish politics right now are really, really interesting, so to say.

ioni: [00:11:26] It's nice to see that the Spanish far right has the same tired and funny jokes as the Romanian and American and the International one.

marina: [00:11:35] Yeah, they are not very original, actually.

ioni: [00:11:39] Ok, then, shall we move on to the main discussion.

lori: [00:11:43] As an intro to our main discussion, I think we can start off with this passage from George Orwell's homage to Catalonia. It's basically a biographical telling of George Orwell's experience as a volunteer in the Spanish Civil War and the fight against fascism. “When I came to Spain and for some time afterwards, I was not only uninterested in the political situation, but unaware of it. I knew there was a war on, but I had no notion what kind of war. If you had asked me why I had joined the militia, I should have answered the fight against fascism. And if you had asked me what I was fighting for, I should have answered common decency. The revolutionary atmosphere of Barcelona had attracted me deeply, but I had made no attempt to understand it. As for the kaleidoscope of political parties and trade unions with their tiresome names, PSUC, POUM, FAI, CNT, UGT, GCI, GSU, IET, they merely exasperated me. It looked at first sight as though Spain were suffering from a plague of initials.” And now, Marina, if you could make sense of this message and tell us about the historical context.

marina: [00:12:58] Yes, of course. George Orwell was an international brigadist during the war in Barcelona and in Aragon. And he is speaking in this quote to read for us about the really poliedric political context of the time, with many different militias, political parties and organizations. And to correctly contextualize this, I think we should go back in time to the beginning of the history of the Spanish Second Republic, which was proclaimed in 1931 after seven years of military dictatorship. In a general election, which is still today polemic for historians. Because some people would say that the republic was not democratically elected. But actually in the main urban centres of Spain, in the local elections, the Republican candidate won. And the Republic was proclaimed on the 14th of April, 1931. It was really, really -- as the quotation from Orwell demonstrates -- it was a really hectic period, not only in political terms. And the different Republican governments tried to undertake different reform projects. For example, one of the most famous is the improvement of public education. The government wanted to establish a new model of public education, which was to begin with a secular system of education and which had this really interesting branch called the missiones pedagogicas -- pedagogic missions -- which were focused in the really, really big problem Spain had at that time in terms of education in the rural areas. So these pedagogical missions were organized to bring culture to the countryside. And even prominent intellectuals, like Federico Garcia Lorca, collaborated with this project of government education.

lori: [00:15:07] Not only was it scarce, but when there was some it was mostly controlled by the Catholic Church, right? At the time.

marina: [00:15:14] Yeah, it was controlled by the Catholic Church. And most of the times it was private. I mean, it was not for everybody. This project of the Republic was one of the first projects in the history of Spain which tried to bring education to the whole population, not only to those who had the economic situation that made it available to bring your children to school, also to say to a good school, to a proper school. So the republic invested a lot of money on educating teachers, for example, and building a lot of public schools. I think I have read somewhere that they had the idea to build at least twenty seven thousand schools, which is a lot. And apart from these education reforms, they also implemented land reform, which tried to erase the big social inequality experienced in the south of Spain, especially in Andalusia.

marina: [00:16:07] Which wasn't a success, so to say. Also because it was interrupted in 1933, I think because the right wing party won the elections and it was kind of a fiasco in the end. So apart from that, for example, women were allowed to vote for the first time in the history of Spain 1933, thanks to the efforts of a Member of the Parliament, Clara Campoamor, which is now one of the most prominent women politicians in the history of the country. So as I was saying, the Republic tried to implement many different and progressive reforms, at least to that time. But at the end, the problem was that it was a bourgeois republic.

marina: [00:16:49] So the different governments had lots of clashes with the workers' movement. And a good example would be the revolution of October 1934, which was supported by the Socialist Spanish party, by the General Workers Union -- one of the main labor unions, that still exists now in Spain -- and also by the CNT (the National Confederation of Workers) -- the main anarchist union. It was a success in Asturias and in Catalonia, but it was violently repressed by the government, which was by then a coalition of different right wing parties.

marina: [00:17:30] All these reforms and progressive ideas that were undertaken by the different -- especially the first and the third -- Republican governments, made a really big part of the army really, really unhappy. And that's why Spain had at that time two attempts at a coup. One in 1932 by the generals and the second one -- which led to the Spanish Civil War -- in July 1936.

marina: [00:17:59] So in the end, I think I could conclude by saying that the Republic never completely managed to solve the economic and social problems of the Spanish society and different sectors of the society were unhappy with the outcomes of the reforms. And of course, the social structure of the country had very big differences between the rich and the poor, and an oligarchy which was mainly concerned with their own problems. So it was a really interesting political project. But many historians would say that it was difficult for the republic to end up being a success.

lori: [00:18:38] And leading up to the second failed military coup which led to the Spanish Civil War, there was quite a lot of tension mounting, because the fascist vigilantes started to basically street fight with all sorts of trade unionists. Assassinations started to flare up. Generals were moved in their postings. And ironically, even though the government kind of knew that something was brewing in the military and Franco was part of it, they still moved him to his colonial posting, where he had very loyal subjects, so to speak. Yeah, quite turbulent times. It's really hard to convey exactly how high the tensions were then.

marina: [00:19:22] Yeah, you can tell the tensions if you read, for example, the transcripts of the sessions of the parliament after the elections in February. Because the elections were won by the Popular Front, which was a coalition made by many different left wing parties. Which decided to unite as a response to the measures taken by the previous government, which was a government formed by a coalition of different right wing parties. So this was kind of a response and it was also supported by different labor unions, including the CNT. So, as you say, the political climate was really, really tense.

marina: [00:20:08] Few days before the coup, a Republican soldier was killed by fascist pistol-men. It's not clear who really killed him. Some historians say it could be a member of the Falange Espaniola, of the main fascist Spanish party. But it's not clear. Anyway, the Republicans answered to this action by killing Calvo Sotelo, who was a prominent right wing politician. And this created a really, really tense climate. And as you say, Franco was moved by the government to one of the Spanish colonies. In the night from the 17th to the 18th of July, there was a coup. First in the military garrison of Melilla, in the north of Africa. And it was followed by different cities in Spain, for example, Sevilla and Pamplona. And it succeeded in many parts of Spain, but not in the entire country. For example, it didn't succeed in Madrid or in Barcelona, or in industrial areas like Asturias or Bilbao, in the Basque country. So many historians today say it was the coup that provoked, in the end, the war. Because Spain was, after the coup, divided into zones. One part was controlled by the republic and the other was under control of the rebels.

marina: [00:21:27] This was also the moment in which the story told by Orwell should be contextualized. Because at that moment, a social revolution exploded in Barcelona. And for almost a year, the city and different areas of Catalonia and Aragon were under the control of the working class. Of the CNT or POUM. And I think if you are really interested in this part of the history of the war, Orwell's novel, it's a really, really good depiction of that period. And as well, Ken Loach's film Land and Freedom -- which is actually based on that book -- in which many, many of the actors are now prominent Spanish actors. But at that time, they were completely unknown to the Spanish public. So it's a nice example.

lori: [00:22:17] And I would like to add for our English-speaking audience, The Blood of Spain by Ronald Frazier is also a really good book. It's basically an oral history of the Spanish Civil War and revolution. So you also have testimonies of Falangists, Carlists and whatnot in it. But it's still a good tale of it.

ioni: [00:22:40] Please correct me if I'm wrong, so usually we use, like this shorthand, to say that it was the war between the nationalists and the Republicans. And when we say Republicans, it's just like an umbrella term because it can mean everything from somewhat conservative liberals, Republicans and even Stalinists, the workers’ unions, all of the anarcho-syndicalists, et cetera, et cetera. While the nationalists themselves, I mean, they were basically the fascists. But some people who are members in UGT, or even the CNT, got recruited into the army. Because when the coup started, they were in fascist occupied land. Yeah. So we'll be using these terms very loosely.

marina: [00:23:26] Yeah. Just one small thing. I prefer to use instead of nationalist faction, rebel faction. It may sound stupid or not very important, but at least in the Spanish cultural memory, if you say national -- we tend to say national faction instead of nationalist, in Spanish -- if you say that, it seems like they had the legitimacy. Like they were the truly Spanish faction. I don't care about that. But for many people it's kind of offensive to say that because as you say, under the Republican umbrella, there were many different types of political affiliations, some of them also conservative. So I would use rebel instead of national, before moving on.

robi: [00:24:16] Can you just please say who the major leftist actors were. For example, what the CNT means and what POUM means?

marina: [00:24:25] Yes, of course. So I think if I start reciting all the different groups, it will be really long. But I will tell you about the main actors.

robi: [00:24:36] It would be a plague of initials.

marina: [00:24:38] Yeah, exactly. That's why I really like this quotation, because it's really, really accurate to the political climate at the time. But yeah. So I will start with the Partido Socialista Obrero Espanol (PSOE), which is the Socialist Party. Which it still exists today. But at least in my opinion, is no longer socialist. Then you have the PCUS. Which is the Partido Comunistas de Union ... Huh? I have forgotten the last letter, honestly. Never mind. It's a Stalinist party in Catalonia. Then you have the POUM, which is the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, which was basically formed by Trotskyists. And which during the war was acting really closely with the CNT. So, the National Confederation of Workers (CNT), which was the biggest anarchist union, which still exists today by the way. Then you have FAI, which is the Federation Anarquista Iberica. What else?

lori: [00:25:44] The UGT.

marina: [00:25:46] Yeah, of course, you have also UGT, which was the main socialist union. Union General de Trabajadores. The General Workers' Union, I think would be an accurate translation. That's why this period is so interesting. You even have anarchist ministers during that time. Federica Montseny, which was a member of the CNT, that was in the government for a brief time.

lori: [00:26:10] Yeah, and Juan Garcia Oliver, as well.

marina: [00:26:13] As well, yeah.

lori: [00:26:14] And they had, I think three ministers. I forgot the third one. Yeah. So Federica Monsteny, right, was a minister of health or something of the sort. Juan Garcia Oliver was like minister of Justice. And I forgot the third one.

marina: [00:26:29] Yeah, me too. Maybe we can add it in the description later. There's a video on youtube of Federica Montseny, forty years after the war, speaking about her role as a minister in the government during the war. Which is quite interesting. I don't know if it has subtitles, but I can check it out and add it, because I'm sure our listeners will be interested in hearing her speak of her experience as an anarchist collaborating with the government.

lori: [00:26:56] And I'll also add excerpts of Juan Garcia Oliver's testimony. Like in an interview after the war ended, he basically said he was completely against joining the government. Yet, he did it anyway, because the union actually decided that they should join. So he didn't want to oppose it, but it was against all of his protestations. To him, it was something... He mentioned something fairly dramatic -- the moment the CNT decided to collaborate with the government, was kind of the day both the revolution and the civil war was lost.

lori: [00:27:30] This was kind of a main tension in the Spanish civil war, of factionalism. Even within the CNT itself, let alone the broader Republican side. At least in the more left parties. Many of them were saying stuff like, OK, we first have to defeat fascism and then we can worry about the revolution. And the other side would say, OK, no, we have to do both. Otherwise we lost anyway.

marina: [00:27:52] Yeah, that's one of the main topics of Orwell's book and of Ken Loach's film. The factionalism and the division of opinion in the leftist media. The two different ideas you have mentioned. If we first should defeat fascism and then make the revolution or if it should be the other way around. That was one of the main problems for the Republican faction. And it's funny enough if you say now in Spain that you are a Republican, they tend to understand that you are either communist or at least left wing. But as you said before, the Republican faction was an umbrella of many different political affiliations.

ioni: [00:28:36] And even at the time -- I hope I'm not misremembering this -- even the anti-authoritarian international movements were very critical of the unions collaborating with the government. I mean, the only reason that the CNT wasn't expelled was because of the great clout it had, and support it had, from other factions that agreed to collaborate with the governments. Like the German anarcho-syndicalist FAUD. I mean, we tend to say, OK, they did this mistake, but we often think it's retroactive analysis. But even at the time this was more or less a common criticism. And like you said, I think the entire left was divided on whether they should just focus on winning the war and restoring bourgeois democracy or building the new world in the middle of the old one.

lori: [00:29:23] Marina, if you could please expand a little bit on the role that these left wing unions had in the Spanish Civil War.

marina: [00:29:31] Yeah, this is actually not my area. So maybe my answer is not as accurate as I would like to, but I could just give a few points.

marina: [00:29:41] For example, in Madrid, the defense of the city was mainly organized -- at least at the beginning -- by militias from the unions. I think in Madrid, mainly from UGT, while in Barcelona, mainly from CNT. And in Catalonia, the role of the unions was completely fundamental because until 1937, the city was under the control of the unions.

marina: [00:30:08] So, yeah, maybe I could just conclude this brief history of the war by saying that after three years of war, Barcelona and Madrid were the last spots to fall. And afterwards we had almost 40 years of really violent dictatorship under Francisco Franco. Which was one of the conspirators of the 1936 coup. And I would say -- and this is closely linked to the current situation of Spain -- that this almost 40 years of dictatorship have marked Spain's political culture. They may be one of the main reasons for the shortcomings that the democracy has now in Spain.

ioni: [00:30:54] The trauma of the war still looms large, but can you focus, for instance, on one particular example and how it still affects discussions today? Like a more concrete topic rather than the overall political atmosphere in Spain?

marina: [00:31:13] I would say that that is the problem with the undiscovered graves of civil war victims and of the dictatorship victims. I would like to make a disclaimer first. I am not an expert in this topic. And if you want to obtain really accurate information, I recommend the website of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory. As well, the Plataforma por la Commission de la Verdad -- Platforma Comisiei pentru Adevăr, in Spain. There you can find lots of information which may probably be more accurate than the brief résumé I am going to give here. So, as I was saying, this whole movement for reparations to the victims is a really, really hot topic here in Spain. Even in parliamentary debates. Because the repression was really violent, as you probably know.

marina: [00:32:07] And it was not only physical repression, for example. And I will tell you about this later in the discussion, all the educational endeavors that the republic carried out were completely cleared and many teachers were parted, some of them executed. For example, there's a really nice film called La Lengua del Mariposas -- The Butterfly's Tongue -- that deals with this problem, if you want to have more information on the topic. So apart from the repression of the teachers, we could speak as well of the thirty thousand babies that were stolen by the dictatorship with the help of the Catholic Church. Which were given to families which were faithful to the dictatorship that's still now in Spain. It's a really, really big topic because a lot of these children, now adults, didn't know they were stolen by the church or by the government.

marina: [00:33:02] But the main group of repressed people were people killed by the national faction -- or by the rebel faction -- during the war and the post-war period. That are now buried in mass graves and are somewhere, we don't know where.

marina: [00:33:18] And the numbers are astonishing. The different historical memory associations say that they could be somewhere between 120.000 and 140.000 people missing. Not only from the Republican side, but also from the Francoist side. But the main difference is that the victims of the Francoist side were searched and were honored during the dictatorship, something that hasn't happened with the victims of the Francoist faction during these almost 40 years of democracy.

marina: [00:33:54] And I think the best example of this topic is the Valle de los Caidos -- Valley of the Fallen -- which is, if I must say, a horrible basilica. If you ever come to Madrid, you should just take a look at it from the road. Because when you go to the mountains from Madrid with a car, you can see it from kilometers. It's massive. It's like a really, really huge cross that is stuck in the middle of the forest. So it was built by Republican prisoners. It was the gravesite of the dictator Francisco Franco until last year and of course, also the gravesite of Antonio Rivera, which was the leader of the falangist party.

marina: [00:34:40] But the worst of it is that together with these two guys, around thirty thousand Republican prisoners are buried in the crypt. And there haven't been many initiatives to at least ask ourselves what to do with these corpses. Because I'm pretty sure the families of these prisoners don't want these corpses to be there, buried together with the dictator. For example, the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations has asked Spain for a plan to look for these missing people. Twice, in 2017 and 2019. But until 2007, the government didn't have any state initiatives for reparations for the victims.

marina: [00:35:27] But as I was saying in this year, the parliament issued a law and I'm going to quote here 'that recognizes and broadens the rights and establishes measures in favor of those who suffered persecution or violence during the civil war and under the dictatorship. This was under the government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, which was a socialist government.

marina: [00:35:49] But this law was abolished by the next government, which was the government of Mariano Rajoy, the Partido Popular, something like today in Germany the Christian Democratic Party. Rajoy didn't give any money to the budget of what is called now the historical memory law. I mean, it was not formally abolished, but there wasn't any money used for these initiatives.

marina: [00:36:15] The plan that the government had was to declare all the Francoist courts illegitimate. To help those who were punished by the dictatorship to commit with the sons and daughters, and great sons and daughters of the victims to search for the mass graves. At least for many people in Spain. This is the most outrageous thing, that none of the graves have been -- for many years -- searched with the help of the government. Maybe we can upload as well a map that was created by ... I don't remember if it was a newspaper or if it was a television channel; of all the mass graves that are still present in Spain. As well, all the Francoist symbols were to be removed from public spaces. I think we don't have any more Franco statues in Spain, but until 10 years ago, you could go to the average small city in Spain and you could see the Franco statue.

marina: [00:37:15] And there was also this plan to give Spanish citizenship for former members of the International Brigades and for the sons and grandsons of victims. And the most important of all, I would say, was the creation of the Documental Center for Historic Memory in Salamanca. This was in 2007. Now -- and I only discovered this a few days ago, and I think it's good news -- before the corona crisis, the current government proposed reform of the law. Which would resignify the valley of the fallen -- the Valle de los Caidos -- and which would promote a census of all the disappeared people. Which I think would help a lot to look for these people.

ioni: [00:38:02] If the whole debate for reparations and heritage... Of course, I don't mean to appropriate any struggle, or to misrepresent. But it's fascinating to see it in the larger context of reactionaries who keep shouting “heritage, heritage”, whenever people ask for their grandparents to be recognized or as we see now, whenever people ask for statues of slave traders to be taken down, et cetera. But at the same time, they're the first to oppose any type of reparations, any type of historical apology, anything at all. I mean, of course, every case is its own situation. But it's fascinating to look at the First Peoples' movement, the Black Lives Matter movement, the reparations movements and see that these don't exist in a vacuum.

marina: [00:38:45] Yeah.

ioni: [00:38:47] Do you know, is this also an international project? Because I imagine -- there are also many volunteers on both sides -- there might be people in the UK and Russia and Germany who are looking for their relatives who disappeared during the war. Do you know if there's any such attempt or connection?

marina: [00:39:07] To my knowledge, many of these associations I have mentioned have former International Brigade members. So I don't know of any only international initiative for looking for disappeared brigadists. I know that many relatives of international fighters are collaborating with these Spanish associations.

marina: [00:39:30] There was -- I think it was in 2010 or 2011 -- on the campus, the Complutense University of Madrid erected a monument to the International Brigades in their main campus, which was vandalized. We don't know by who, but we can imagine. So, yeah, the international brigades are somehow present in this fight for memory, but I don't know of any initiative that is only international. Of course, their memory should be restored as well.

marina: [00:40:00] I remember, for example, I worked for two years in a laboratory at my university, which was collaborating with these associations. And we were working with corpses from people who were shot in Cuenca in the south of Spain. And one of the corpses belonged to a former brigadist. We could tell it, because he had his international brigades card, so to say, in one of his pockets. And it was quite impressive to see.

ioni: [00:40:29] Also -- because, of course, there was lots of infighting going on -- I wanted to know, for instance, if one of the persons fighting on the Republican side is also known to have, like, weird and covert connections or to be one of the torturers or stuff like that. Are they automatically barred from applying for these reparations?

marina: [00:40:51] I'm afraid I cannot answer your question. But the problem here, if you are looking for reparations, is that the government is not going to help you. I mean, until now. Now that there's this initiative, maybe things will change. But there has been a refusal from the part of the different democratic governments to help victims. And that's why most of the movement is in the hands of private associations like the ones I mentioned at the beginning, the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory and the Platform for a Truth Commission. And also smaller associations. For example, the mass grave where my great granddad is supposed to be buried, was excavated by the association Recuerdo y Dignidad -- Memory and Dignity -- which is a small association based in Soria.

marina: [00:41:39] Sometimes the regional government or the city halls helped these associations with small subsidies, but that's all. There's no general initiative on the part of the government to help the victims. And all the trials against Franco's collaborators have been I don't want to say useless, but yes, useless. At least in Spain. For example, the judge Baltasar Garcon -- which was a really polemic judge -- his attempt to judge crimes against humanity here in Spain were prevented or interrupted. The only successful attempt to pursue these criminals was made in Argentina by different associations who initiated the lawsuit in the Argentinean tribunals, with the help of the Argentinean judge Maria Servini de Cubria, on the crimes against humanity here in Spain. For example, among the accused was this guy, Jose Antonio Pacheco, commonly known here as Billy el Nino -- Billy the Kid -- which was one of the worst torturers of the dictatorship, especially at the end in the sixties and seventies. And who died last month from Coronavirus.

robi: [00:42:48] At least something good came out of it.

ioni: [00:42:51] Make here a comrade corona joke.

robi: [00:42:55] Yeah. I was really conflicted whether to make a joke about it.

marina: [00:42:58] Yeah, I feel the same. Don't worry.

marina: [00:43:01] Also, this Argentinian initiative is working since 2016 on the murder of the famous poet Federico Garcia Lorca, which was shot in Granada at the beginning of the war. And who must be buried somewhere around Granada. But we don't know where. And they are working on this case as well.

marina: [00:43:22] The most important thing when it comes to the movement for reparations, as I said before, is that the Spanish government never collaborates. Or only did for a really short period during the government of Rodriguez Zapatero. But when the Argentinean justice contacts Spain during these 10 years, the Spanish government has never accepted to help or to collaborate. And this is something quite common here in Spain. Since the democracy was reestablished, there's been no public initiative to reparate the past.

Intermezzo

lori: [00:44:18] One of the main points of what we've discussed so far during this episode is that the Civil War brought an influx of volunteers from all over the world to Spain, most of them on the Republican side. Militants, anarchists, communists and social Democrats, working class people, journalists, dissidents or reckless adventurers from France, Germany, the USA, all the way up to Japan, flocked to Spain to join the fight against fascism. So one might say that Spain was truly in their hearts. We wanted to find out more about the Romanian brigadiers, since we know there have been at least a few of them. Who were they? How were they organized? What military operations that they take part in? What little information is available on the subject has been distorted by the latter day propaganda of the nationalist communist regime to fit its narrative. As such, we asked our friend and previous podcast guest, Alex, to track down the elusive Mihai Burcea, a historian and activist who studied the subject for years. Eventually, the two of them met and decided to sit down for a talk. We added this to the conversation. So here's what we found out.

lori: [00:45:30] The Romanian brigade had 377, mostly men, but also including five female nurses. About a quarter of these were members of the Communist Party of Romania and its various satellites and dissident groups. While most belong to the Hungarian MADOS, the Social Democratic Party and even the Radical Peasants' Party. There was much ethnic diversity as well, including Jews, Romanians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Russians, Roma, Serbians and Germans. Class-wise, most were working class people such as carpenters, textile workers, drivers and nurses. They departed for Spain 1936, which was a tense year in Romania as well, with street fights between nationalists and workers engulfing the country. The Communist Party was the one that arranged this transfer, but since it was acting illegally at the time, this meant that they had to leave in several waves, sometimes as groups and other times individually, most often through Czechoslovakia. Many took advantage of the 1937 International Exposition of Art and Technology in Paris and asked for passports. Once in France, they were picked up by the International Red Aid and transferred to Spain via bus. In Spain, they were garrisoned and Albacete, where they received military training. The Romanian group here was led by Iuliu Lunevski and later by Petra Borila. After the brief training they were sent to the front.

lori: [00:47:03] The Romanian brigades fought all over Spain, including Madrid and the Battle of the Ebro River in 1938. Less than 100 volunteers died in battle, most of which were buried in the Fuencarral cemetery near Madrid. After the war, a few fought with the French Resistance, while the rest formed Soviet backed guerrillas during World War Two and carried out sabotage operations against the Romanian army, which was at the time still allied with the axis. For some, the fight against fascism was never over, such as the case of the physician David Iancu, who left for China to fight against imperial Japan after the end of World War Two.

lori: [00:47:46] Many former volunteers were assigned to various ranks and positions within the new regime. Of course, a trace of misogyny can be traced there, as well, as the female nurses received only marginal roles compared to the men who occupied various positions, from army generals to state officials to criminals and butchers for the system of repression. Some of those that wanted to further the socialist policies or criticized the state capitalist direction were sidelined and marginalized. Unlike many of the neighboring countries, however, they all escaped the Stalinist purges of 1949-1959, when many of those who fought in Spain and France were eliminated as Titoists or pro-Western imperialist spies.

lori: [00:48:30] That, folks, is the short version, if you'd like to find out more, we will include a link to our full discussion with Mihai Burcea in the episode description. The conversation is in Romanian, but you can also find a link to an English -- text only -- translation.

lori: [00:49:05] Hold the press, folks. I guess the stream, but we've just been informed that there was also a group of anarchist brigades from Bucovina taking part in the war. Now, hopefully we'll get the chance to learn more about this and even maybe talk about it in a future episode of ours. Stay tuned.

---

andra: [00:49:34] So now that we know more about the context, tell us the story of your family.

marina: [00:49:40] Ok, so basically both sides of my family were somehow involved in the war, of course, as I imagine most Spanish families were involved. I will split it in two parts. First, I will just briefly address my paternal family, and then I will go to the story of my maternal family, which is more long to tell because my maternal grandparents were adults already when the war started.

marina: [00:50:07] So in my paternal family, my granddad -- he was a child when the war started, he was about 10 or something like that -- his dad was a member of the UGT, the socialist trade union. And this is curious - he appears in the famous photographs of Puerta del Sol -- the main square in Madrid -- the day the republic was declared in 1931. My dad is unable to tell me who he is, but he is there somewhere.

marina: [00:50:36] He fought in Madrid during the war. As I told you before, the defense of Madrid was mainly in the hands of the unions' militias, at least at the beginning of the war. In retaliation for his participation in the union, his wife's hair was shaved after the war, and all the family had a really hard time in the first years of the war because of hunger and diseases. My great grandmother died really soon after the war, so my granddad had to start working really, really young. And in the case of my grandmother, she was also really young when the war started. She was seven, I think. And she has this really tender story about her dad's business. They owned a lamp shop in the center of Madrid -- really, really near the Puerta del Sol -- which was destroyed by a bomb during the bombings. So they had to flee to Valencia, where the government had fled as well. And they spent the rest of the war there. And they came back after the war and she had a plan to study chemistry in the university.

marina: [00:51:44] But of course, she was unable. Because after the war, university was accessible only to people with enough money. And there weren't many women, at least in the first years of the dictatorship, who were able to access university studies. So that's about my paternal family.

marina: [00:52:03] In the case of my maternal family, I know most of this information thanks to my mom and my uncle. But I never met my granddad or my grandmother because they both died before I was born. So in July 1936 -- that is when the war started -- my granddad, Antonio, was studying physics in Madrid, but at that moment he was in Soria for holidays. Soria is a really small city in Asturia, north of Madrid. If you ever come to Spain, I recommend you visited it, because it's like a fairy tale place. It could appear in one of Tolkien's books or something like that. And he was having holidays there when the war started and Soria was in the part of the country which was controlled by the national troops.

marina: [00:52:54] So after that, he was recruited by force by the rebel army of Franco. So at the same time, he's da -- my great granddad -- Aurelio, who was sixty four years old, was arrested in Soria on the 22nd of July by the Requetes, which was a Carlist extreme right militia. And then, according to his prison dossier, he was, quote unquote, 'freed'. He was shot. On the night of the 16th of August.

marina: [00:53:22] And there's this gossip told by the great son of one of his coworkers that he had apparently tried to telegraph some information about the rebel army to the Republican authorities in Madrid. But I'm not sure if I should believe this story, because it's coming only from one source. So he was the head of the telegraph office in Soria. And he was a Republican, but he wasn't involved in any political organization. But from my mum, I know that he liked the Partido Socialista Obrero Espanol, the PSOE.

marina: [00:53:57] So he was shot without trial near Soria's cemetery, together with other members of the intelligentsia of the province. Members of the town hall, public officers, a doctor, an anarchist journalist, and various members of trade unions. Actually, the only, so to say, monument that somehow remembers this event was put there in the cemetery by CNT, by the anarchist trade union, after the war. Like ten years ago, or something like that.

marina: [00:54:27] One of these associations who are fighting in the movement for reparations here in Spain, Recuerdo y Dignidad, excavated in 2018 the area of the cemetery where all these people are supposed to be buried, with no results for now. So no corpses appeared. And I find quite funny that the authors of the only book on their repression in this area of Spain, which is called La Repression en Soria durante la guerra civil -- The Repression in Soria during the civil war -- called my great granddad 'secular apostol'. I don't know why, but they say that he was a prominent member of the intellectual milieu of the city and he was called secular apostol.

marina: [00:55:13] And there's another anecdote I find interesting about his personality that apparently while he was working in the telegraph office Coruna, in the north of the country, he helped to detect a priest who was secretly telegraphing information to the Germans, in the First World War. So he must have been quite a character. So that concerning my great granddad.

marina: [00:55:37] His older son, Aurelio, which was twenty nine years old, he was a member either of CNT or POUM, we are not completely sure. And he was working as well as a telegrapher in Valladolid, a Castilian city, like Soria. And this is one of the cities where the coup succeeded. So the last thing we know about him is that -- according to the Castilian newspaper El Norte de Castilla -- he was arrested on the 9th of August for being a dangerous element. This is a curious rhetoric resource that the Francoist propaganda used a lot. And most probably he was as well shot. But we don't know where he was buried. But a common practice during the war was to bury those who were murdered in the ditches near the road. So he must be somewhere in Castilla, maybe in Burgos. We don't know.

marina: [00:56:31] His sister, Marina, was working as a teacher in a small village in the province of Soria. She was one of these teachers hired by the republic in their effort to improve the educational system in Spain. And shortly after the coup, she was fired and she was kicked out of the house she had as a part of her contract. So after the war, she somehow managed to finish her degree in philosophy and letters in Madrid, and she barely survived teaching private lessons in post-war Madrid.

marina: [00:57:05] And in the fifties, she fled to America. And for the next 20 years, she worked as a Spanish teacher in different universities and she befriended many Spanish exiles.

marina: [00:57:16] And now we come to my grandad, Antonio. He has a story that, in my opinion, sounds like a film. Yeah, I'm not kidding. You will hear about it. He escaped from the Francoist Army when they were arriving in Madrid in the autumn or the winter of 1936. He escaped through the front lines in what is today the Ciudad Universitari -- the University City -- the main campus of the Complutense University of Madrid. He went through the front lines and he joined the Republican Army and fought with them until the end of the war.

marina: [00:57:52] My parents and my uncle always told me that he didn't like to speak about that period that much, but he always said that he didn't kill anybody. But we know that he fought in various fronts and in the battle of the Ebro River in 1938, which was one of the battles of the war. And in that battle, a splinter of a bullet hit him, but remained in his arms until the 60s when he suddenly started to feel pain in one of his arms and went to the doctor. And the doctor said, hey, you apparently have something in your arm. And this something was a splinter of a bullet, which had been there for almost 30 years.

marina: [00:58:35] So in March 1939, when the war was almost over, he was in Alicante on the coast, which was one of the last Republican strongholds. Where many people were waiting for a British boat, which was supposed to stop there and pick up the many refugees. But instead of the British boat who never showed up, Italian fascist troops arrived to the city and many people began to commit suicide, either by shooting themselves or just jumping into the water.

marina: [00:59:07] My granddad was arrested and condemned to death by firing squad. He was sent to one of the many concentration camps around the city. He remained there for three months until somehow -- nobody has been able to tell me how -- my grandma, Sylvia, managed to convince a relative who was a member of Franco's army to commute his death penalty.

marina: [00:59:31] And I have another anecdote regarding this period, because apparently the prisoners in that concentration camp only received lentils as food, which is a really common stew here in Spain. We eat a lot of lentils. And he would eat lentils every day with really tiny pieces of stone. After three months eating only lentils, lentils remain his favorite food for the rest of his life. I don't know how is that possible? But he loved lentils. Yeah.

marina: [01:00:03] So he was released. He finished his degree in physics and he asked his sister, Marina. He remained in Madrid. He survived teaching private lessons and working later for the National Research Council, which in terms of scientific research, was a wasteland. Like most of the Spanish research endeavors until the end of Franco's dictatorship. He was living in Madrid with my great grandma and his little sister, Felicia, who was still a child and died at some point in the 40s. And this is more or less the story of my maternal family during the war.

ioni: [01:00:43] This might be in poor taste, but maybe as an intermezzo here, besides the music would make, you know, like a fake movie trailer narration about your uncle's life or dramatic music and exaggerated narration. OK.

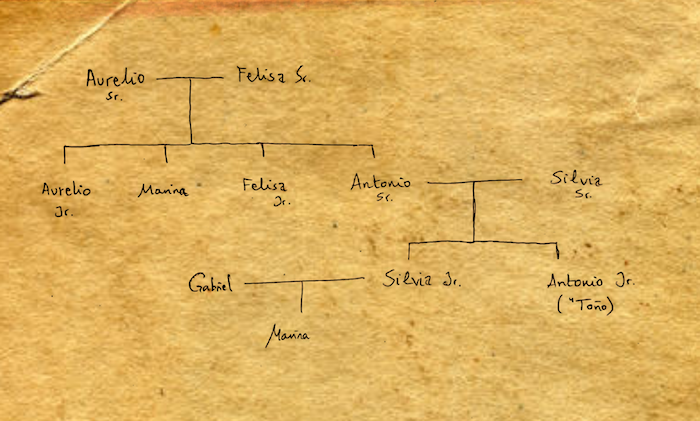

ioni: [01:01:01] We should also, like, make a very basic sketch of the family tree, because for people who find it too confusing, because maybe they'd want to see exactly who we are talking about.

marina: [01:01:13] Oh, yeah. Ok, if you agree, I would just make a draft version with all the relatives. Because apparently my family, they were not really or when it comes to names, because all of them are Felicia, Sylvia, Aurelio or Antonio. Which is kind of confusing. So I can draw one for you and send it.

robi: [01:01:34] I wanted to remark that, but I didn't know if it was appropriate.

marina: [01:01:38] No, but this is really common. This is really common. Come on. My grandparents were Antonia and Sylvia. The names of their children, Antonia and Sylvia. And I was supposed to be Sylvia as well. But my mom said, no, no, no, no, no. No more Sylvias, please. This is going to be really confusing.

lori: [01:01:52] It's like One Hundred Years of Solitude.

marina: [01:01:54] Yeah, exactly. Exactly. That's a good comparison.

ioni: [01:01:58] And also, maybe in parentheses you can add like their political affiliation with a party or union. That would make it easier to follow.

marina: [01:02:05] Yeah, I can do this only in the case of my great uncle and my great granddad. Because my great granddad was a Republican... I mean, maybe he was a leftist, but a really soft leftists. Like, my mum, she always says that he followed some kind of system of ideas she would call anarcho-feudalism. Which is completely made up, but I like the term. Like. Yeah.

ioni: [01:02:35] The story of the people committing suicide. It reminded me of the death of Walter Benjamin. Well, it was a bit later, but it was similar when they were running from the German army and it was mostly a group of Jewish refugees and leftists.

ioni: [01:02:49] And the Spanish authorities said that they would be handed over either to the Italians or the Germans. And Benjamin committed suicide and another person tried to commit suicide. Another artist, I forgot who. And this shocked the Spanish fascists so much that they simply allowed the people to get away.

marina: [01:03:07] Yeah, I mean, it's kind of similar. What I know from Alicante, is that they were hoping for a British boat to show up. It was apparently organized by the International Red Cross with help of the British government. But the Francoist faction, which was, I mean, they were in power, actually. I think Alicante was the only remaining Republican city. They didn't allow the boat to stop. And instead, the Italian fascist boats appeared. So many people just killed themselves out of desperation. I mean, they were going to be arrested anyway and most of them killed. So, yeah, it's kind of the same as with Benjamin. But in this case, the fascist didn't admire the bravery of the Spanish refugees, I think. Because most of them were detained and brought to concentration camps. Which still exist. But most of them, they are not arranged as museums. Which I think would be a nice idea.

ioni: [01:04:07] Ok, so this is more or less an abridged version of what happened to your family during the war. What happened to them in the post-war period and how did they handle it?

marina: [01:04:22] So, as I said, my granddad was surviving on private lessons during the first years of post-war. But at some point at the end of the 40s or the beginning of the 50s, he received an offer to work at the University of Caracas, in Venezuela. And so then he proposed to my grandmother, to Sylvia, which was also her cousin. This was a common practice, I guess, in all Europe -- or at least in Spain -- until recently. To have marriages between cousins.

marina: [01:04:54] So they decided to start a new life outside Spain as many other Spanish citizens. He moved there in advance. My granddad, Antonio, he moved there perhaps one year before his wife, and he discovered that there had been some kind of misunderstanding because the position he was offered wasn't that of a professor, but a janitor. So he was the janitor of the faculty for some time until the mistake was solved. And after that, he taught physics in Caracas until the 70s when my whole family went back to Spain.

marina: [01:05:27] So later, my grandma moved to Caracas with some other Spanish and Venezuelan teachers. She founded a school because she had studied pedagogy in Spain in the 30s. And as far as I know, she taught Spanish literature and Latin. Interestingly, for example, my edition of The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco has some notes of her near the Latin paragraphs. That's something I really enjoyed the first time I read the book because I didn't have any knowledge of Latin at the time.

marina: [01:05:58] So the students in this school were both Spanish and Venezuelan. But to my knowledge, this school had the option for the sons and daughters of Spanish exiles to study the bachillerato, which was the secondary education in the Spanish system. For example, instead of studying Venezuelan history, they could study only Spanish history or a mix of them. I'm not really sure. But what I know is that it was a school for Spanish and for Venezuelan students. So in the 60s, my mom, Sylvia and my uncle Antonio were born.I don't have much information about their life in Venezuela in those years, apart from the fact that my grandparents never interacted a lot with Venezuelan people.

marina: [01:06:44] I mean, almost all their friends were Spanish exiles and they never fully integrated into our society, maybe because they were still affected by the trauma, as many people who fought in the war or who suffered the war when they were in their 20s or 30s. They remained in Caracas until the death of the dictator, who died on the 20th of November 1975. And was buried in this megalomaniac tomb that I mentioned before, the Valley of the Fallen.

marina: [01:07:19] The same year, my great aunt Marina -- the Spanish teacher who was teaching in the United States -- came back from America and she took up again her duties as a rural school teacher, being one of the last retaliated Republican teachers to see her position restored. She was working as a teacher until she retired. I don't know how long, but for a few years. And I have always found it really astonishing that after so many years teaching in a completely different environment, she really wanted to go back to her former work as a rural teacher. So that concerning Marina.

marina: [01:07:59] My grandparents, Sylvia and Antonio. I know this might be confusing because the names are repeated all the time. They came back to Spain in 1976. They came back to Madrid and my mom and uncle finished high school and went to college here in Madrid. And the story of many attempts they made to recover Spanish citizenship is rather curious one, but at the same time sad. As Venezuelan citizens they wanted to apply for a residence permit. But the Spanish authorities told them that it wasn't necessary because they were of Spanish origin. So therefore they wanted to renew their national ID card because the last one had expired like 20 years before. But they were told that in order to do that, they needed the residence permit. So it was kind of a conundrum. It was impossible to obtain either the national I.D. or the residence permit. So in the end, my granddad renounced his Spanish citizenship in order to receive his pension as a professor in Venezuela. And his daughter, my mother Silvia, obtained the citizenship when she married my dad. And I am not sure how my uncle obtained the citizenship, but I know that my grandmother tried to delay that moment as much as possible until my uncle was no longer of military age. And actually, he later joined the anti military movement against the mandatory military service in Spain.

marina: [01:09:31] So my grandmother died in 1985 after a very long cancer. My granddad, at the same time, with the help of some kind of Republican ex-combatant organization, was trying to obtain formal recognition from the government of his rank in the Republican Army. Something which, at least in my opinion, will have happened since taking into account that the International Brigades, the members of the party and trade union militias and the troops of the army, which was loyal to the republic, had died defending democracy. An imperfect one, but a democracy. And it would have made sense for the current regime, which is another democracy, to look at the Second Republic as its immediate predecessor and not the Francoist dictatorship.

marina: [01:10:18] So in the end, my grandad died in 1989. The certificate recognising his rank arrived shortly after his death. And after that comes, I would say, the saddest part of the history. Of the story. Because it shows how, as I said at the beginning of the discussion, the Spanish justice system and the Spanish government is not willing -- or at least wasn't willing until now -- to help the victims of the dictatorship or the war.

marina: [01:10:50] So after coming back to Spain, as I said before, my great aunt Marina was working as a rural teacher for some years, and then she retired and she died in 2008. I think she was 99 or 100. She had a really long life and -- I must say -- a really interesting life. So in 2011, the Spanish tax agency contacted my mom and my uncle to ask them to pay the inheritance tax and according to them, they were the heirs of an inheritance Marina had left. But they weren't aware of this.

marina: [01:11:25] They didn't know anything about this inheritance. So they hired a lawyer to start the process to obtain the heritage. And the thing is that according to Spanish law, if any of Marina's siblings had been alive, they were the real heirs. But, obviously, they had been dead for a long time. But the court didn't recognize the tax agency documents that recognized my mother and uncle as heirs. Neither their cousin's testimony about the death of all of Marina's siblings.

marina: [01:11:57] So therefore, the court didn't recognize their right to Marina's heritage because there weren't any death certificates certifying the deaths of my great Uncle Aurelio, who was shot in 1936, and my great Aunt Felicia, who died in the first years of post-war, I think of tuberculosis.

marina: [01:12:15] So after a few years, my Uncle Antonio decided to try to demonstrate that his uncle and aunt were dead. He obtained the death certificate of her aunt by contacting her parish in Madrid. But Aurelio's case was more difficult, because during the war fascists didn't use to issue death certificates of the people they killed. So with the help of public defenders two years ago, my uncle managed to obtain a death certificate of his uncle in Valladolid, the last place where we know of him alive. The public edict in which my great uncle is declared dead says that he's 'paradero desconocido desde el 8 de agosto de 1936', So that his whereabouts are unknown since the 8th of August 1936.

marina: [01:13:05] After that, my mom and uncle could receive the heritage and paid the inheritance tax. In this same period, my uncle contacted the association Memory and Dignity in Soria, and so he learned that the mass grave where his granddad, Aurelio, was thrown after being shot was going to be excavated. And he joined the excavation team.

marina: [01:13:26] So I think this story I just told is a good example of the attitude of the Spanish justice system about the cases related to the Civil War. For me, the whole story sounds like a joke. Because nobody in their right mind would believe that a man who was born in 1907 would have been still alive in 2011. And because everybody knows how Franco dealt with prisoners belonging to the left wing organizations during and after the war. But just as the Spanish government never collaborated with the Argentinian judge in prosecuting Francoist war and post war crimes, a great majority of the Spanish justice system doesn't want to recognize the Francoist crimes here in Spain.

marina: [01:14:08] For the vast majority of the Spanish politicians it is just as Pablo Casado -- which is the president of the Spanish Partido Popular -- what this guy said in 2015. All these stories are just 'batallitas del abuelos', grandpa's war stories. So I wonder what kind of democratic society and culture we can build if we bury the story of all the repression performed by the rebel army during the war and by the dictatorship during the next 40 years. And this is something that is still being discussed here in Spain. And it's a painful topic for many people.

robi: [01:14:45] One might think that this effort or endeavor to uncover this hidden history of people who have disappeared ... One might ask, what significance does it have now? Like how many, 70, 80 years? Because it's something that happened very long ago. But it is very clear from the things that you have said, this hidden history on one part, it has still material consequences today. In your personal example, it was the difficulty with having this heritage from your aunt Marina recognized.

marina: [01:15:16] Yeah.

robi: [01:15:17] So this is also a material consequence that the civil war is having still now. But it also obviously has a very important cultural, symbolic, personal importance, right. To know what is the faith of family members, parents, grandparents? And I'm also guessing for some people who are religious or spiritual, it has other layers of meaning. As you said, about the example of the poet Lorca, it also has a national cultural meaning. And maybe if you can say a few more words about this. The meaning for you of this movement for reparations.

marina: [01:15:52] Ok. So, for me personally, it has an important meaning. Maybe not as much as for my mother or especially my uncle. But in the end is the history of my family. And I think it's right to demand to the public authorities to recognize those who were killed unjustly and fighting for freedom, for democracy, for a project that was important for them. Which was really trying to establish some kind of social justice, which was not possible before the second republic in Spain.

marina: [01:16:28] I mean, I would like to know where my great granddad and my great uncle are buried. And to have maybe a public recognition that they were shot. For example, if you read the record of the prison where my great granddad was imprisoned, it says that he was freed. It doesn't say he was condemned to death. He was theoretically free. So that on the personal part.

marina: [01:16:53] In terms of national culture, I think it will be also really important to recognize the sacrifice of these people and to help the relatives. Because not all relatives are interested in looking for their grandparents or great grandparents or their parents, but many people are interested in doing it. For example, to my knowledge, the family of Lorca is not especially interested in looking for his body. They are much more interested in recognising his legacy as a prominent poet in the history of the Spanish literature. And to recognize that he was killed because of his ideas. But they are not interested in the material Federico Garcia Lorca, so to say.

marina: [01:17:35] And of course, you mentioned the heritage. This is also important. The dictatorship stole the fortunes of many people during the war and during the dictatorship. And it's funny that, as you say, almost 80 years after the war started, there's still fights on the part of victims trying to receive what was theirs. Even if it's not a great deal compared to other fortunes.

marina: [01:18:03] But it was the Spanish justice system which was trying to prevent my family from receiving their heritage, not a fascist party or something like that. It was the justice system that was preventing them from receiving their heritage. So, yeah, I think this is something which Spain should address in the next years because there hasn't been any serious attempts in the almost 40 years of democracy that we have now. And it's important also, for example, when it comes to explain this period in public school. To my knowledge, most teachers do not address this period properly because the program is so long that it's impossible to reach the 20th century. So, yeah, it's a matter of national interest, I would say.

ioni: [01:18:51] You mentioned that your great aunt Marina, the Spanish teacher, returned to Spain in 1975.

marina: [01:19:03] Yeah.

ioni: [01:19:04] Do you have any information if she was planning on doing this before she heard the Franco's death, or if she rushed a lot to be there really first. Because this was late November.

marina: [01:19:16] I'm not sure. I would say she wasn't, because she was really established in the USA. She had friends, she had a life there. So I don't think so. I'm pretty sure she wasn't planning to come back. I mean until the dictator was dead. Most of the exiles came back after he died.

andra: [01:19:36] I'm very glad that you were able to discuss the fascinating story of your family history. I was wondering, what are your plans? If you want to follow up and dig up some other things about your family and even publish it or write about it now.

andra: [01:19:58] And also, how did this personal story influence the way you later were interested in the leftist movements? And how does the family history influence you personally in your activism?

marina: [01:20:14] Wow, that's a good question. I have always had the idea to write something about this, because I don't want it to be lost. And I like to write.

marina: [01:20:25] Now I don't have time because I'm writing my thesis, but I would like to dig more into this history and to write maybe an essay or something like that. But I would need time. For example, to go to archives and so on. For example, it will be interesting to do some research on the political affiliation of my great uncle. Because most of the archives of the anarchist and socialist unions were erased after the war. The fascists took all of them. So now I know that there's some work being done on these kinds of archives. And I would need to work on that if I was to write something about my family. And that's a project I have for some point in my life.

marina: [01:21:12] And about influencing my personal engagement with activism and so on. Of course, this has influenced me because I grew up hearing stories about the war and hearing stories about my grandparents in Venezuela and here in Spain. And in different ways they were always engaged with fights for social justice, as well as my dad now. So, of course, this was an influence for me. And I remember going to different events organized by associations which are fighting for the right to remember and to have the lives of these people recognized. So, yeah, definitely it was important for me. And I guess my interest in the political uses of the past comes from here as well.

marina: [01:22:03] Because in the public sphere, it seems that nothing of this happened. I mean, if you are, for example, in a conversation with friends or family and you somehow start speaking about this, somebody is going to tell you all you are just bringing up again batallitas del abuelos, your granddad's battles. And I feel it shouldn't be like that.

ioni: [01:22:25] So we could say that family gatherings are pretty tense in Spain, right?

marina: [01:22:33] Yeah.

marina: [01:22:34] And I find it pretty offensive that the public servants say something like that. If you don't speak Spanish, maybe you can't get the meaning of batallitas del abuelos. But they are using the diminutive. Batallitas is fight or war. And they are using 'ita', which is like little battles of your granddad. As if you were speaking about something which is nonsense and not important. And this is something that comes up in the political discourse quite a lot on the part of parties like Partido Popular. And I feel this is really offensive. At least you could address the topic in a different manner.

marina: [01:23:12] And they are always saying that people who are looking for their relatives in the common graves or ditches, they are just opening old wounds. This never stops. And the only state endeavor that tried to fix this was abruptly interrupted by a right wing government. So, yeah, family conversations are quite tense. Not in my case, because my family is pretty boring, because we all more or less have the same political feelings. But in other families, this is quite big.

marina: [01:23:45] Like in my partner's family, you cannot speak about these kinds of things. Because you are going to be attacked. Or even in class. Like I remember when I was in college, we had a seminar on modern history, the 20th century. And we had this trip to the Valle de los Caidos, and it was really polemic. Because, of course, I think as historians, it was a really nice idea to visit it and to have as a tour guide a professor who is an expert on this kind of public memory issues. But there were a lot of people who thought that this is just batallitas del abuelos, we should close this kind of wound. And this is not important. This is a monument for the common memory of Spain. At the same time, you are seeing these two megalomaniac tombs of Franco and Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera. And the Guardia Civil is even there. The rural Spanish police is guarding the place. So it's pretty polemic, yeah. Sorry for the long answer.

robi: [01:24:43] But I think more in the spirit of Ioni's comment, if all your grandparents and some of your great grandparents were alive, that would make for a very tense family dinner. For me, all of my grandparents are still alive. And when I was a child, I think three or four of my great grandparents were also alive. So in principle, I could have had that kind of dinner, but none of my parents or grandparents or great grandparents were political in any way. So in a sense it is fascinating to me to have so many factions or leftist factions present in one family tree. Because in your paternal family, they are more on the socialist side and in your maternal family they are more on the anarchist side.

marina: [01:25:21] It's really interesting now that you mention that. For example, in the case of my paternal grandmother, when Franco died and Spain had its first democratic elections, she started voting the right. Really, really soft right party. But now she's voting Izquierda Unida [United Left], which is, OK, not far left, but left. Izquierda Unida is a coalition of left wing parties, of left wing organizations. So there has been like an evolution. And this is also interesting. That she started voting really shyly because everybody was really, really, really scared of another civil war when Franco died. And now she has slowly turned to the left wing options.

robi: [01:26:08] You know, there's that bit of wisdom that when you're young you're progressive, when you get older you become conservative. Fuck that.

marina: [01:26:16] Yeah, exactly.

robi: [01:26:17] As time passes, I just go more to the left. And older comrades have said the same thing, that as time progresses, you have less things to lose. And why not just go full radical left?

marina: [01:26:28] That's it. I mean, I wouldn't say she's radical left, but she's at least voting left wing options.